Cheri Smith

Cheri in her London Studio

Your work frequently explores themes of animality and wildness. How do these ideas manifest in the pieces you are presenting for Under the Laurels?

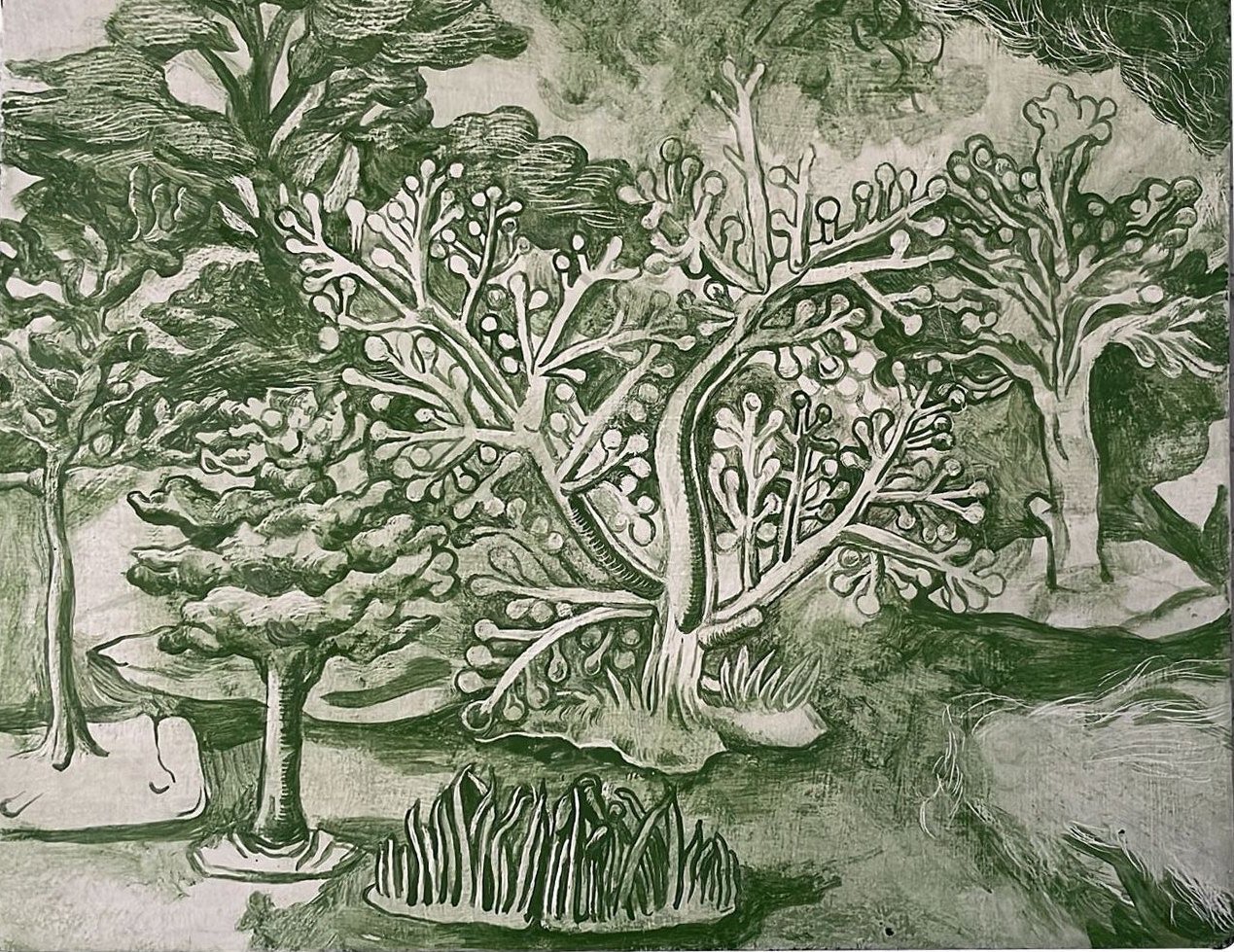

Cheri - I think that my deep underlying interest in that which is alive, animal and elemental is what unites the pieces I am presenting. There is a particular sense of touch and sensitivity to texture, whether working in pencil or egg tempera. I think this is perhaps most keenly felt in the portraits of my dog, in which drawing her from close observation came almost to feel like the act of stroking her fur.

You use a range of materials like oil, egg tempera, and glue distemper in your paintings. What influenced your choice of medium for the works featured in this exhibition, and how do different materials shape your artistic process?

Cheri - I enjoy the process of making paint from pigment and binders such as oil, egg or glue. It emphasises the material nature of pigments, which are really just crushed pieces of the natural world - such as rocks, plants, shells and beetles. This understanding of paint as being something formed of and from the earth certainly shapes the paintings themselves. Many of my pieces included in Under the Laurels are drawings made in pencil on paper - to me this feels similarly earthly and material - the most immediate, sensitive medium there is.

Your paintings often depict animals with a blend of playfulness and violence. What is the symbolic role of these animals in your work?

Cheri - Animals can have an endless stream of different meanings and associations, which change from one person to the next. They defy any attempt to easily pin them down, and I am interested in that ambiguity and ambivalence.

You’ve spoken about the ‘unknowability’ of the natural world, could you talk a bit more on this aspect of nature?

Cheri - My practice is deeply rooted in the natural world, driven by a curiosity to encounter it and continued attempts to understand it. I am often returning to Thomas Nagel’s essay What is it like to be a bat?, which vividly explores the impossibility of comprehending the experience of a lifeform so different to our own. Of course, I still continue to try.

Your work seems to grapple with the tension between human understanding of nature and the autonomy of the animal world. How has this theme evolved over time?

Cheri - This is something I am always aware of and thinking about. I worked as a visitor assistant at the Natural History Museum for many years, and came to feel that all this collecting, classifying and displaying probably reveals more about humans than it does about nature. It’s like our knowledge is something imposed over the top rather than feeling intrinsic or innate. At the same time, I find the history of how we have looked at and attempted to understand the natural world deeply compelling, providing a bottomless well of inspiration. Ultimately I try to afford everything the same level of care and scrutiny in my paintings, whether stone, plant, animal or human. All kinds of beings are often muddled up together, forgetful of any supposed categorisations or hierarchies.

You’ve had residencies in diverse locations like Jamaica and Italy. How have these experiences of being immersed in different environments influenced your work?

Cheri - I feel incredibly fortunate to have undertaken residencies in such places; their influence will last a lifetime. In Jamaica I found myself struck by the sense of deep time embedded in the landscape - I snorkelled over coral reefs brimming with life, then walked over ancient fossil coral embedded in the earth. I learned from locals how much the coral reefs have visibly diminished in their lifetime. In volterra, Italy I felt a deep affinity for the landscapes and wildlife. It was magical to be visited by hares and deer while painting trees, rocks and rivers. I definitely found that the relationship between observation and imagination in my work strengthened during this time.

With animals playing such a central role in your work, what kind of research or observation do you conduct to inform the animal behaviours and interactions in your paintings?

Cheri - I am always seeking nature out, and spending time looking closely. I lift up stones to find out what’s underneath. I hang bird feeders in my windows and sit quietly drawing the birds that visit. I bring small treasures back to my studio which inform my paintings - bits of fungus, bark, feathers, dead bugs, hatched eggshells and empty snailshells. I draw my dog, and my plants, and the people I love. In this sense my research is deeply personal, always rooted in my own direct encounters and observations.

Are there particular books or paintings you return to?

Cheri - I reread Surfacing by Margaret Atwood every few years, when I feel a tugging at me to follow its nameless protagonist into wildness and madness. I adore everything I have read by Joy Williams, and I hold her strange, spiralling worlds always close to my own as I work. Living in London, I am lucky to have access to some of my favourite paintings - I visit Pisanello, Sassetta and Giovanni di Paolo in the National Gallery as though catching up with old friends.

Like Dora Carrington, there is a rich and idiosyncratic world within your work, are there themes or landscapes you plan to approach in the future?

Cheri - With each body of work I make in the studio, new veins of thought open up, and I find myself readying to make the next more ambitious in terms of depth and complexity. The landscapes I have been working with recently have become increasingly psychological and some themes bubbling to the surface of my thoughts include entanglement, isolation and survival.