Martina Ziewe

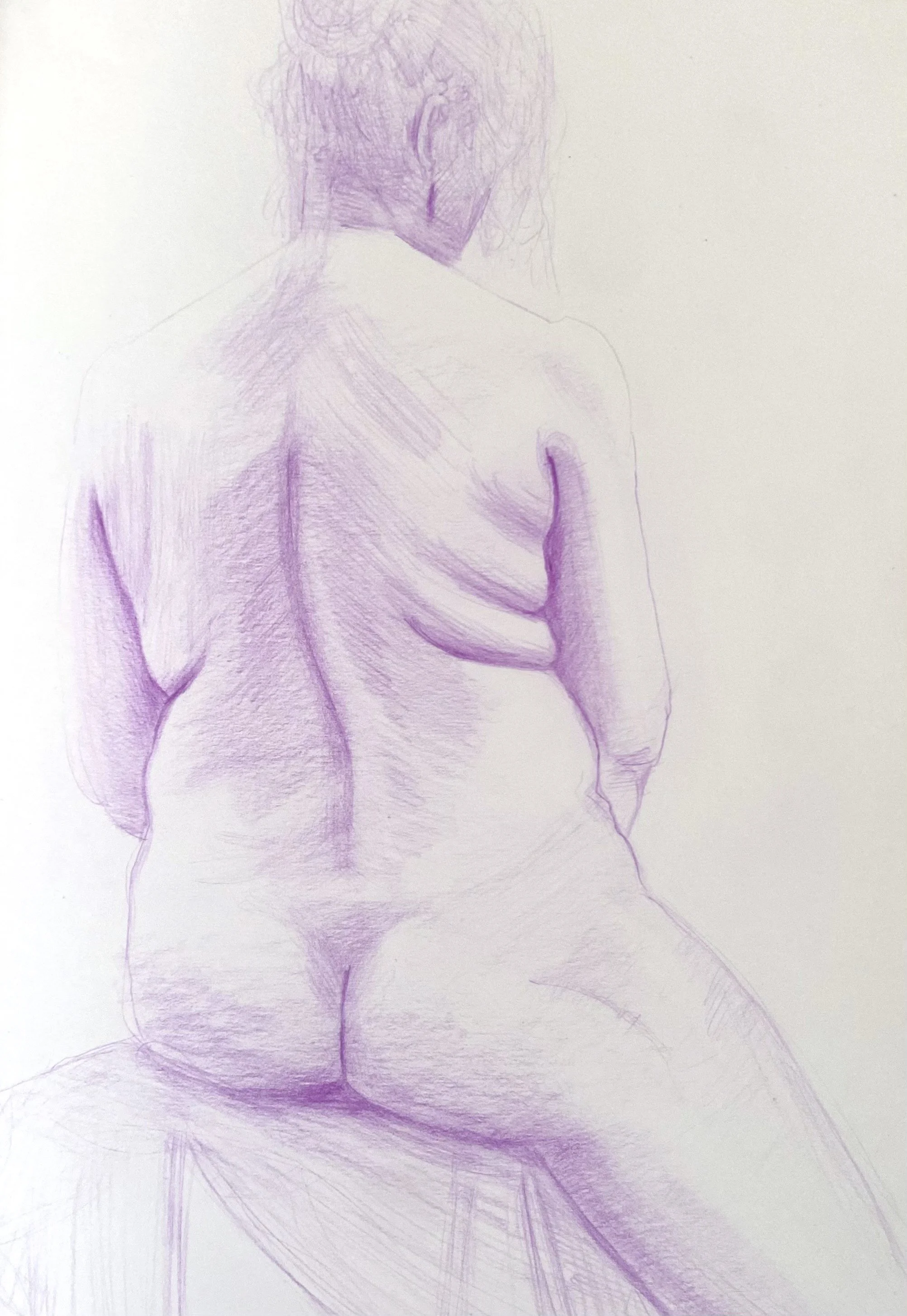

Ahead of next appearance at Drink and Draw, we sat down with Martina to talk about her journey- from her yoga and meditation teaching to her studies at the Royal Drawing School, and how all these experiences shape the unique, supportive communities she helps to build through her creative practice.

Martina Ziewe

We’re delighted to welcome back Martina Ziewe as the guest artist for our next Drink and Draw session on Wednesday 15th October. Martina’s practice moves fluidly between art and mindfulness practise spanning life modelling, facilitating drawing sessions, yoga, and meditation. At the heart of her work is a commitment to creating environments where people can listen inwardly, explore creativity without pressure, and connect meaningfully with one another.

Ahead of leading the Drink and Draw, we sat down with Martina to talk about her journey from her yoga and meditation teaching to her studies at the Royal Drawing School, and how all these experiences shape the unique, supportive communities she helps to build through her creative practice.

Martina Ziewe, Catherine

Your work spans art and mindful practices - from life modelling and facilitating drawing sessions, to teaching yoga and meditation. How do these different roles inform each other, and how do they shape the kind of communities you're helping to build through your creative practice?

Martina - The underlying thing all these practices have in common is the holding of space and of people. I encourage people to listen inwardly, to respond and make decisions according to what is right for them, through the tools I share in the yoga and meditation sessions. I have the intention to create warm, welcoming spaces for people to let go, to listen, to observe, to practice awareness and to enter a flow state.

Community is a very important thing to cultivate and nurture, it is especially pertinent in these incredibly challenging times. Co-creating spaces where people can learn to trust, listen inwardly and make their own decisions based on their lived experience of being human is something I actively encourage. My classes are very client centred, I check in regularly to inform how the sessions can change according to the learning of the students. Another important aspect of the sessions I hold is the playful and fun element. Sharing moments of joy and silliness helps bring lightness to our lives. Resting, slowing down, being still, listening, observing and resourcing ourselves in this way can have a positive impact, helping us come back to our everyday lives perhaps a little better equipped to deal with the challenges we are faced with and hopefully therefore have a ripple effect and a positive impact on others we come into contact with.

These practices weave together and inform one another as everything does. I learn from working with all different client groups and what they bring. In yoga I work with older people mainly. I also work in community spaces with adults with learning disabilities, physical disabilities and mental health challenges. I learn a lot from these spaces as they are less conventional and people tend to not conform to societal norms.

How do these shape the kinds of communities you are helping to build?

Martina - In the chair yoga and meditation groups I teach in local community centres, (for almost a decade now), many people made friends from meeting there, and go out together one to one and in groups, they have gone on holidays together, they give one another lifts, visit one another if ever in hospital, check in through WhatsApp groups if someone isn’t at class. It has grown to be a tight knit, strong, kind and supportive local community, all from practicing yoga together in a circle every week (sometimes more). Doing this on a Monday morning weekly sets a tone for the week ahead with intention and care, so this weekly class has a trickle effect into other aspects of their lives.

In the life drawing community it is also important to be welcoming, as it can be intimidating coming to draw as a beginner, so part of my job is to invite people in to feel relaxed and welcome, helping create a low stakes environment. Attendees to the life drawing room sometimes live alone, have life challenges, or very busy lives, all sorts of things going on.

Listening to music, while drawing together, drinking tea, talking and sharing. Nurturing a creative, inspiring space is a wonderful thing to be able to offer to my local community. Holding space where people can sharpen their mindful and creative practice. There is such a special atmosphere in the room when we are all quiet and focusing on a shared practice synching up our nervous systems, our breath and our heart beats. I feel this to be a positive contribution I can offer with my background and personal practices. These spaces gives us a little time out from the horrific news of the days worlds events, to respond simply to the living being in front of us and to honour them. We have a variety of excellent models who bring so much to us in their presence, often Artists themselves.

Again, people make friends in these sessions, we are encouraging of one another and we inspire one another. These spaces can help boost peoples confidence. And all the sessions can enhance peoples health and well-being on a number of levels from the physical to the spiritual.

To summarise a little here, the Drawing Room, who I run sessions under:

“Our ethos is providing welcoming and friendly sessions as well as expert tuition so that anyone who comes through our doors – be they complete beginners or professional artists – can have the freedom, guidance and space to develop their practice and discover new ways of seeing and working”.

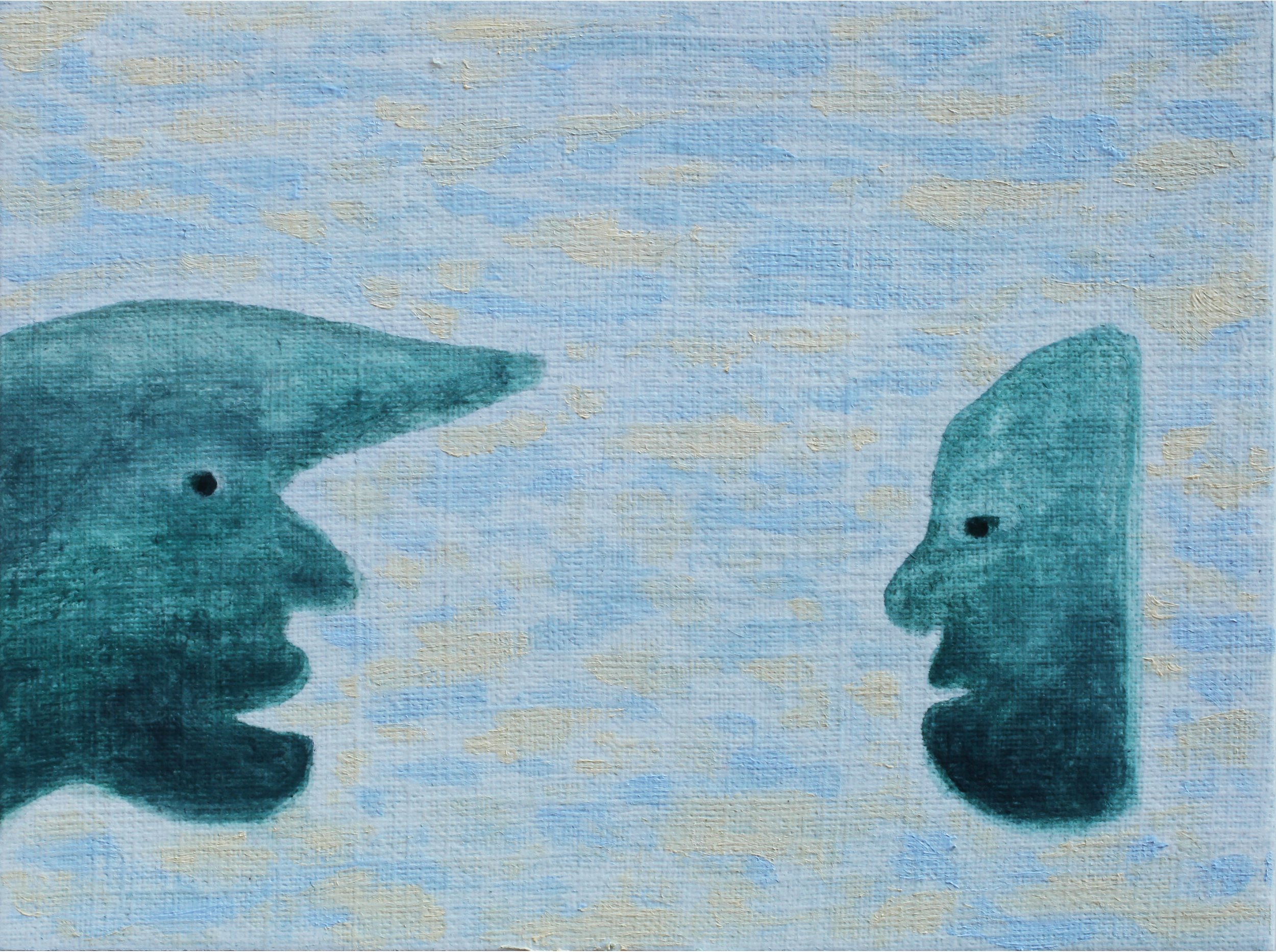

Wooden Sculpture by Martina Ziewe

You’ve recently completed the Royal Drawing school’s intensive drawing course – can you tell us about your experience?

Martina - It was a very positive experience. I went to university to study Fine Art at Kingston University when I was 19 and I felt like I was going off to uni for the first time again. Having a whole week to be a student was something I embraced and am very grateful for. There were a variety of sessions to choose from. It challenged me and I learned new things. I highly recommend the Summer School intensive, to fully immerse yourself in drawing intensively all day everyday! The things I learned there I will carry with me into my practice going forward, such as some of the exercises we tried I can take into my own sessions. Shout out to Artist David Gardner who is an example of a compassionate Artist, Practitioner and facilitator, I learned a lot from his Narrative Drawing Day both in my learning experience and in the way he holds space for others. The other sessions I chose were the Drawing Lab and Human Anatomy. This experience of the Drawing School made me want to be a student again. I wrote about each days learning on my instagram if you’d like to read further about my experience. Generally the school taught me unconventional ways of drawing especially in the Drawing Lab experience with Charlotte Mann.

Life modelling can be an incredibly vulnerable and powerful experience. What has it taught you about presence, acceptance, and being seen - both by others and yourself?

Martina - Life modelling is a meditation. When I get into a deeper meditative state I first become aware of the energy within me, and this can extend to picking up on the energy of people present and the broader field of the room. The positions I come into reflect how I am on the day, sometimes strong and self possessed, at other times vulnerable and quiet and all sorts in-between. Depending on where one is on the day being seen can be empowering and an act of giving to the creative process to inspire. It can also be a sensitive area depending on ones internal landscape. It is a very human humbling experience and this is the gift you are sharing in your humanity and presence to the artists who are drawing.

One has to be present because of the sensations that arise in the body, particularly when the pose is more challenging, this can be interesting for building mental resilience and stamina. In life modelling you can explore the edge as well as choosing surrendering gentler poses. So one must be present to what ever arises, hence a meditation and a practice of acceptance to what arises mentally and physically and whatever levels I tune into on the day.

What are you reading at the moment?

Martina - One day, everyone will have always been against this - Omar Ali Akkad

& Tending Grief - Camille Sapara Barton

Finally, what’s on your studio playlist? Give us 10 tracks - either what you’re listening to right now or an all-time top 10 for working in the studio.

Martina - I am not very good at favourites generally, but here are few that I have played lot in no particular order picked from various studio playlists…

Yumeijis theme - from ‘In the Mood for love’ soundtrack - Shigeru Umbayashi

Whiskey Story Time - Alabaster DePlume

Rola Azar - Ya Taala'in al-Jaba

Sea swallow me - Cocteau Twins

To li - Jojo Abot

Keytar (I was busy) - Jemma Freeman and the cosmic something

The Sailors Bonnet - The Gloaming

On the nature of day light - Max Richter

Song for Zula - Phospherescent

More Pressure - Kae Tempest, Kevin Abstract

Jasmine Simpson

We’re delighted to welcome Jasmine Simpson as the artist host for our September edition of Drink & Draw!

Jasmine is an artist whose practice is deeply rooted in her heritage. Growing up surrounded by the rich ceramic traditions of Staffordshire, she developed a fascination with form, texture, and storytelling that continues to shape her work today. Her imagined animal forms and myth-infused figures carry a distinctive blend of tenderness and strangeness, inviting viewers into worlds that feel both familiar and otherworldly.

Jasmine in her studio

Born in Boston, Lincolnshire, and raised in Stoke-on-Trent, Jasmine is an artist whose practice is deeply rooted in her heritage. Growing up surrounded by the rich ceramic traditions of Staffordshire, she developed a fascination with form, texture, and storytelling that continues to shape her work today. Her imagined animal forms and myth-infused figures carry a distinctive blend of tenderness and strangeness, inviting viewers into worlds that feel both familiar and otherworldly.

Jasmine’s creatures are steeped in narrative, drawing inspiration from the folklore and craft traditions of her hometown, and they provide the perfect spark for our September Drink and Draw session. With her guidance, participants will explore intuitive mark-making, character, and texture in a relaxed, friendly environment.

This event marks the start of a new season for Weald Contemporary’s Drink & Draw Club—and we couldn’t think of a more exciting artist to lead the way.

Let’s start with your journey from Stoke to Sussex. How has that move influenced your practice, and what led you to make the shift geographically and artistically?

Jasmine - Stoke has an amazing heritage and has allowed me to hone my skills in ceramics and the arts but Sussex has lots to offer artistically. Not only with amazing job opportunities with the Matt Black Barn but with the wider connections and creative communities such as Matt Black Barn, Weald contemporary, Bloomsbury group etc. There is a history of artists here and a buzz about art that attracted me.

You’ve recently shown work in several exhibitions, can you tell us about some of the themes or ideas you've been exploring in your recent pieces?

Jasmine - My most recent piece ‘Untrainable’ explores the intersection of gender roles, domesticity, and rebellion. By reimagining the traditional Staffordshire ceramic dog —typically a symbol of loyalty, domestic order, and femininity—I challenge the societal expectation that women must conform to idealized domestic roles. In other works I’ve been exploring nature and fragmentation. Looking at the material qualities of clay, how it is morphed, fragments and breaks, and linking this to the idea of patching together memories of the past and how we have fallen out of touch with nature and how we can bring the pieces of those memories together to reconnect.

What have you been up to this year so far?

Jasmine - This year has been a pretty busy one. Alongside making for Galleries I started the year busily making for Ceramic Art London, which took place in May. This was My first time exhibiting for this particular show and it was a wonderful insight into larger scale exhibition hall type shows- a type of show I haven't done in a long time. It was also a great opportunity to rub shoulders with some of my favourite ceramic artists and well known people in the circuit.

In June I was involved in a group show called 'Behind The Closed Doors' in Safe House 1 in London. A show about the hidden power dynamics of family life through everyday objects. It was here where I exhibited 'Untrainable', A mixed media installation exploring the weight of inherited domestic roles and the persistent struggle for female autonomy within the home. The work features an angry ceramic dog tearing up her handicrafts and smashing crockery whilst sitting in a demonic armchair, laundry draped across the back and morphing into a grotesque face. I've also made an effort so go and see shows and galleries this year, like 'Abstract Erotic' at the Courtauld Gallery, 'Jenny Saville: The Anatomy Of Painting' at the National Gallery and Finally Seeing The Charleston House (now it's a stone's throw away).

And to top it all off I got married this month!

How would you describe your current practice, and what continues to drive or challenge you in the studio?

Jasmine - The exploration of ceramics is endless and I'm constantly finding new ways of working with it. Even after all these years I’m still just beginning to see clay through new lenses with viewpoints given to me through my exposure with more artists, communities and nature after moving south. I’m also looking through my old sketchbooks at some older ideas I’ve had with fresh eyes and seeing what sparks.

There Are Devils In My House by Jasmine Simpson

Finally, what’s on your studio playlist? Give us 10 tracks - either what you’re listening to right now or an all-time top 10 for working in the studio.

Deep Blue Day- Brian Eno

The Pot- Tool

Tezeta - Mulatu Astatke

Coffin Nails- MF Doom

Embryonic Journey- Jefferson Airplane

Beeswing - Richard Thomson

Parade - Rone

Flying Bamboo - Nitai Hershkovits, Mndsgn

Long Long Silk Bridge - Susumu Yokota

Welcome to paradise- greenday

Alexander Johnson

Weald Contemporary is thrilled to welcome the talented Alexander Johnson as the next guest artist for our upcoming Drink and Draw session on Wednesday, 7th May. Known for his expressive style and dynamic use of colour, Johnson brings a fresh and imaginative energy to everything he creates. We caught up with him in advance of the session.

Alexander Johnson holding ROSA Magazine Issue 12, Spring 2025, cover featuring his artwork.

Weald Contemporary is thrilled to welcome the talented Alexander Johnson as the next guest artist for our upcoming Drink and Draw session on Wednesday, 7th May. Known for his expressive style and dynamic use of colour, Johnson brings a fresh and imaginative energy to everything he creates. This special event offers a unique opportunity to meet the artist behind the work, gain insight into his creative process, and sketch alongside him in an inspiring, relaxed setting. In this interview, we dive into Alexander’s artistic journey, his influences, and what attendees can look forward to during the session.

Your work has long drawn from music, film, and literature as much as visual art. In an era when algorithms shape so much of what we see and hear, how do you keep your influences intentional rather than passive?

Alexander- Good question! I sometimes feel my senses getting poisoned by unsolicited digital content but we are all to some extent influenced by the targeted algorithms whether we like it or not. To temper those influences, I constantly block content that I either find banal or annoying (for whatever reason) so that on my Instagram feed I’m left mainly with things I’m already interested in - 1970’s graphic design, B&W social documentary photos, old paintings - so that now what I see on my feed aligns quite closely with what I would choose if I was I to go into a library for books. I have always ignored cultural things that are hugely ‘popular’ with the mainstream; if it’s very popular it’s quite probably worthless.

What are you reading at the moment?

Alexander- I’ve been reading a book called Women Painters by Lucy Davies. Prior to that I’d just finished a book on Orientalism and the artist Jean Léon-Géròme and I’ve got my nose in a couple of Goya monograms, which I’m referencing in the new paintings. I read art books in the day and then novels before I sleep. Currently re-reading M Train by Patti Smith for my book at bedtime. Also anything by Olivia Laing.

“People often tell me my work feels like someone reaching out,” you once said. In a world dominated by screens, do you feel painting still offers that tactile emotional link that’s getting lost elsewhere?

Alexander- Painting is an activity unique to humans, to an extent everyone can relate to a painting because everyone will have made a painting themselves at some point in their life. I think post-covid there has been an increase in respect for artisans who use ‘old-fashioned’ (ie. Pre-digital) skills to make something tangible, a physical object. Programmes like the Pottery Showdown, Sewing Bee and the Repair Shop have become hugely popular because people love to watch skilled workers doing their thing, myself included. Equally, when you know an object is the result of hours of skilled human concentration, I think most people, even children, instinctively realise its value.

Photo: M. Rawlinson

The digital world is so transient I can’t really take it seriously. The day after a ‘new iPhone’ drops it’s already out of date. But the Mona Lisa or Picasso’s Guernica will never be out of date. I think art collectors and people in general will still want paintings, objects, things they can hold, feel and hang on the wall to decorate and enrich their home space. I think collectors appreciate the continuum that starts with the first oil paintings in the 14th century and runs a continuous line through the Renaissance connecting to what contemporary oil painters are making today. People won’t want to buy stuff that they can make themselves at home on their laptop using AI and a laser printer. So AI doesn’t worry me at all, nobody can make one of my physical paintings apart from me and that won’t change in my lifetime.

You’ve often spoken about the influence of punk – the Clash, DIY bands, the rawness of the scene. Does punk as a philosophy still guide your choices when you’re working with Old Master references and historic subjects?

Alexander- I still consider myself a punk. By that I mean, I just get on and do stuff in my own way. I take what I need from the past, a composition here, a character there, then glue them back together in my head, then paint it. A lot of the old masters were punks in their day, they were rebels who didn’t follow rules and challenged the established order, they copied things from the past and remade them to their own design. These artists were difficult, confrontational and brave people who were often in trouble with the church and their wealthy patrons for not doing what they were told. All good artists have a punk sensibility really, they don’t care much what went before or what is ‘popular’ at the time, they dance to their own tune and make their own rules. The only thing they have in common is hard work.

Can you tell us a bit more about your current solo exhibition Where are we Now? At Rogue Gallery and what you are currently working on?

Alexander- I aim for at least one good solo exhibition a year in the UK. The recent exhibition came about after a friend introduced me to Ray Gange the director at Rogue Gallery in St Leonards. I’d been painting the lead models for about a year which Ray saw on Instagram and liked. I was interested in showing at his gallery because I liked some of the artists he had shown there in the past. Ray and I got on immediately and I subsequently found out that he had been a roadie for the Clash in the late 1970’s at around the time I first saw them aged 15 and decided to go to art college. This gave us a platform of respect and mutual understanding that made me feel completely confident in working with him because I knew he’d get the references in my paintings and be open to leftfield ideas, changes of direction and wouldn’t be fearful of more challenging content in the work.

CEASEFIRE!

Oil on canvas, 160 x 180cm (2025)

You once said, “You don’t want to give people everything: you want to give them little bits of something.” That feels especially poignant today, when so much art is consumed in a swipe or scroll. How do you create work that asks people to slow down, look longer, maybe even come back to it again?

Alexander- try to create images that have an initial impact but then enough depth of detail to keep you looking and enjoying new things. I want to leave people some space to feel their own way through a narrative painting, so I offer hints and clues rather than setting out a completely understandable narrative. I do this by playing with colour, composition, scale (often enlarging things hugely) and just not doing the obvious or the expected. I don’t think too much while I’m actually painting. Though I’m slightly wary of the expression, I will admit that I have to get myself ‘in the zone’ before I start, this will often mean two days reading, choosing records, building up a wave of energy in my head and then eventually transferring that onto the canvas. I don’t really know what happens and I don’t need to know, as long as I can still paint it I’m ok.

Thanks Alex! finally, please create a 10 track studio playlist - this can be recent favourites or a greatest hits!

Alexander- This is completely impossible for a music lover like me, but off the top of my head!

Peter James Field

Peter James Field is an artist whose work bridges the gap between fine art and illustration, capturing the essence of his subjects with precision and depth. Whether painting for gallery exhibitions, illustrating for renowned fashion brands, or chronicling daily life in his decade-long visual diary project, his work is marked by keen observation and a unique personal touch.

Peter James Field is an artist whose work bridges the gap between fine art and illustration, capturing the essence of his subjects with precision and depth. Whether painting for gallery exhibitions, illustrating for renowned fashion brands, or chronicling daily life in his decade-long visual diary project, his work is marked by keen observation and a unique personal touch.

In this interview, Peter shares insights into his creative process, from finding inspiration for his portraits—including his piece featured in Perfect English: Small and Beautiful—to navigating the balance between commissioned and self-directed work. We discuss his materials of choice, the impact of music on his artistic flow, and his experiences working with figures like Yeside Linney and Alexander Nilere. With a passion for storytelling through imagery, Peter's reflections offer a fascinating glimpse into the world of contemporary portraiture.

Those attending our Drink and Draw session at Ghost at the Feast on Wednesday, April 2nd will be learning from Peter firsthand - we can’t wait!

Peter at his Brighton studio

One of your portraits is featured in Ros Byam Shaw's newly released book, Perfect English: Small and Beautiful. Could you share the process behind finding your subjects?

Peter - That particular painting depicts Pallant House Gallery Director Simon Martin, who lives in a lovely flat which was photographed by Ros for her book. This was actually a commission – I know Simon and he approached me in 2019 to ask if I’d do a small painting of him.

I don’t take on a huge number of commissions, they probably make up about a quarter of my overall painting time. The rest is self-directed work, and I’m always on the lookout for people who might be interesting subjects. I often ask friends/acquaintances to sit, or sometimes do callouts on social media for people who might be willing to volunteer. It’s generally a process of ‘casting the net’. I tend to work a lot from photos, which I always take myself, so I meet lots of people (usually a lot more than I end up painting) and search for some fairly indefinable spark of inspiration in those encounters.

L-R: Simon Martin, Portrait by Peter Field. Page and Cover of Perfect English: Small and Beautiful by Ros Byam Shaw.

You undertook a visual diary project, which lasted over 10 years and resulted in the book ‘No Bulb in my Lamp’. How did this long-term endeavour influence your artistic development?

Peter - The diary began as a one week college project, aimed at encouraging us to make space for daily observational sketching. Once I started drawing every day, I found I was looking more intensely at the world, and saw that there was the potential for beautiful or thought-provoking drawings in even the most mundane scenes. For me, in a way, it was a case of ‘the more mundane the better’. Drawing helps one experience things directly, and provides a mindful space, together with ways to experience reality afresh. I suppose the diary confirmed to me that I am primarily an observational artist – but not seeking to provide a photographic rendering of reality, instead filtering visual experiences through my own moods and idiosyncrasies. To quote Emile Zola: ‘Art is nature seen through a temperament.’

Pills, page taken from No Bulb in my Lamp by Peter Field.

You will be teaching our next Drink and Draw session in April, what can the attendees expect?

Peter -It’s going to be a really fun evening, with a fantastic model, and lots of varied poses, short and long, to allow everyone to just experience the pleasure of drawing. I’ll be on hand to provide lots of support and encouragement. You don’t have to be a seasoned sketcher, or to have done any life drawing before. The evening is just about having a go, and enjoying the process.

Could you discuss your choice of materials, particularly your preference for mechanical pencils and small sketchbooks, and how they complement your style?

Peter - I hate sharpening pencils, particularly when I’m on the go! Mechanical pencils are therefore obviously great – whether it’s with small 0.5mm leads, or fatter clutch pencils which take a whole thick stick of graphite. Small sketchbooks can easily be fitted in a coat pocket, so they’re great as well.

Generally, I am quite a precise and small-scale sketcher – I love a clean, fine line. At art college the tutors were always telling me to ‘work bigger’ and ‘get messy’, but interestingly whenever I did attempt to work outside my comfort zone on huge sheets of paper, it never felt like ‘me’.

I think we all have to find the style of mark-making (and by extension the materials) which suit us, not just as artists but as people. I am quite a shy, hesitant, cautious person, so it’s no surprise to me that I work in a very planned out, neat way.

What are you reading at the moment?

Peter -I’ve been reading a 1970s Japanese novel called The Box Man by Kōbō Abe. It’s a surreal Kafkaesque little book about a man who retreats from society by wearing a cardboard box on the upper part of his body. I’m sure I fantasised about doing that when I was a shy teenager...

Your recent portrait of artist Yeside Linney, titled "Yeside" (2023), was featured in the Herbert Smith Freehills Portrait Award exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Could you share the inspiration and process behind this particular piece?

Peter - Yeside is an amazing artist, and an extremely enthusiastic lover of art – she's a cheerleader for so many artists on social media, which is how I got to know her. I asked if she’d sit for a possible portrait because she seemed fascinating and I just wanted to meet her. I think this is how a lot of good portraits begin; a simple fascination with another person and a desire to connect in some way. It wasn’t until I met Yeside that I realised she’d already sat for over a dozen other artists!

I met her at her home and we took a few hours to just explore a lot of options in terms of pose and lighting. I ended up being fascinated with her hands and wanting to find a way to put them in the image.

After my sitting with Yeside, I went through a process of making lots of sketches, ending up with this composition. My paintings take quite a long time – but this one was fairly quick and only took about three months of on-off work.

I love the work you did for Comme des Garçons. can you tell me more about that and other brushes with fashion you have had in the past?

Peter - The Comme des Garçons piece was a fairly straightforward magazine illustration commission for a Japanese fashion magazine, where they sent me photos of a piece they wanted rendered in a beautiful colour pencil style. I’ve done hundreds of magazine assignments, but that one really became a huge stand-out favourite in my portfolio, for myself and for those who commission work. I’ve done a fair few illustrations for fashion brands over the years – including for Hogan, Sunspel, United Arrows, Charles Tyrwhitt and Tommy Hilfiger. A couple of years ago my painting of Alexander Nilere was borrowed by Manchester City Art Gallery for their show ‘Dandy Style’ which was a survey of men’s fashions across the last few centuries.

Comme des Garçons Jacket, Brutus Magazine.

Do you view your illustrative work as distinct from your fine art painting and printmaking, or do they overlap in approach and intention?

Peter - I do view them differently. The obvious difference is that illustrations are commissioned works, usually for print, so they are never about my personal expression. I do a lot of portrait illustrations and I rarely if ever get to meet the subjects, and am always expected to deliver a certain amount of flattery and/or strict adherence to the source photos. Also, these drawings (they’re usually pencil illustrations) are made to be scanned, emailed as digital files, and reproduced at a certain size. So the ‘original’ might look great, but that’s irrelevant, it has to reproduce well at its given page size (and the client will rarely, if ever, see or care about the original).

None of this is meant to be a criticism of illustration, it’s just a different beast. In illustration it’s often quite nice and comforting to have the reassurance of working to a strictly defined brief, especially when it's with a good art director who can push you to produce something out of your comfort zone.

In my fine art painting work I always have a face-to-face encounter with my sitters, and the resulting work expresses some aspect of my personal passion. And unlike illustration, where the end result is basically dictated, I go into each and every painting feeling fairly uncertain where the process will take me or what the end result will look like. This is where so much of the joy lies – it's always a process of discovery.

Even in a commissioned painting, where I may make certain compromises with a sitter, I still maintain the awareness that this is not an illustration, and that it therefore has to fit into my vision and provide me with some creative nourishment (partly because a painting takes so long, and it would be depressing to approach it any other way). If a commission can’t do that, I won’t take it on.

Your portrait of Alexander Nilere, dressed in a striking patterned suit, features a particularly compelling composition. When working with sitters you've personally invited, do you take on the role of art director, shaping the setting and their attire, or do you indulge in a more organic approach?

Peter - Generally speaking I take the organic approach. In the case of Alexander, I had met him a few times before and knew that he had a very bold, distinctive fashion sense (often making his own clothes). It was always my intention to capture him in one of his amazing suits, but over and above that I didn’t go into the sitting with a plan. I think it’s important for a portrait artist to be open-minded - I’m looking for the uniqueness of the sitter, and I won’t know what that is until I experience it. With Alexander, this turned out to be a slightly pensive, reflective pose he assumed – which summed up something about him. He dresses flamboyantly but is not, as a person, particularly showy or driven by ego. I think the portrait succeeds in communicating these two aspects of Alexander, and perhaps hints at the ways in which one serves the other. His colourful clothes help give him a confidence which may not always come too naturally. His dress sense is not boastful, and I think the portrait communicates that.

Alexander Nilere by Peter Field.

I know music is another big passion of yours, please make a 10-track studio playlist:

Peter -I have extremely broad tastes, but when I’m painting I try to choose fairly emotional music that seems to help me get into a flow state. This playlist gives a flavour of the sort of thing I’d be putting on for a painting session.

Tom Scotcher

We caught up with Tom Scotcher ahead of our greatly anticipated Drink and Draw session to talk art, inspiration, and what to expect from the Weald Contemporary Drink and Draw experience!.

As we gear up for our very first Drink and Draw Club, we’re thrilled to have artist Tom Scotcher at the helm, guiding us through an evening of creativity, conversation, and inspiration. A graduate of the Royal Drawing School, Tom’s work has been showcased at Piano Nobile Gallery as part of the prestigious Ruth Borchard Self-Portrait Prize, and you might have spotted him on Sky Arts: Portrait Artist of the Year. In 2024, his talent earned him the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grant, a major honor for emerging figurative artists.

With teaching experience at Camden Arts Centre, Brighton MET, and City & Guilds of London Art School, Tom brings both passion and expertise to the table. We caught up with him ahead of the session to talk art, inspiration, and what to expect from the Drink and Draw experience!.

Tom Scotcher in his studio space, Brighton.

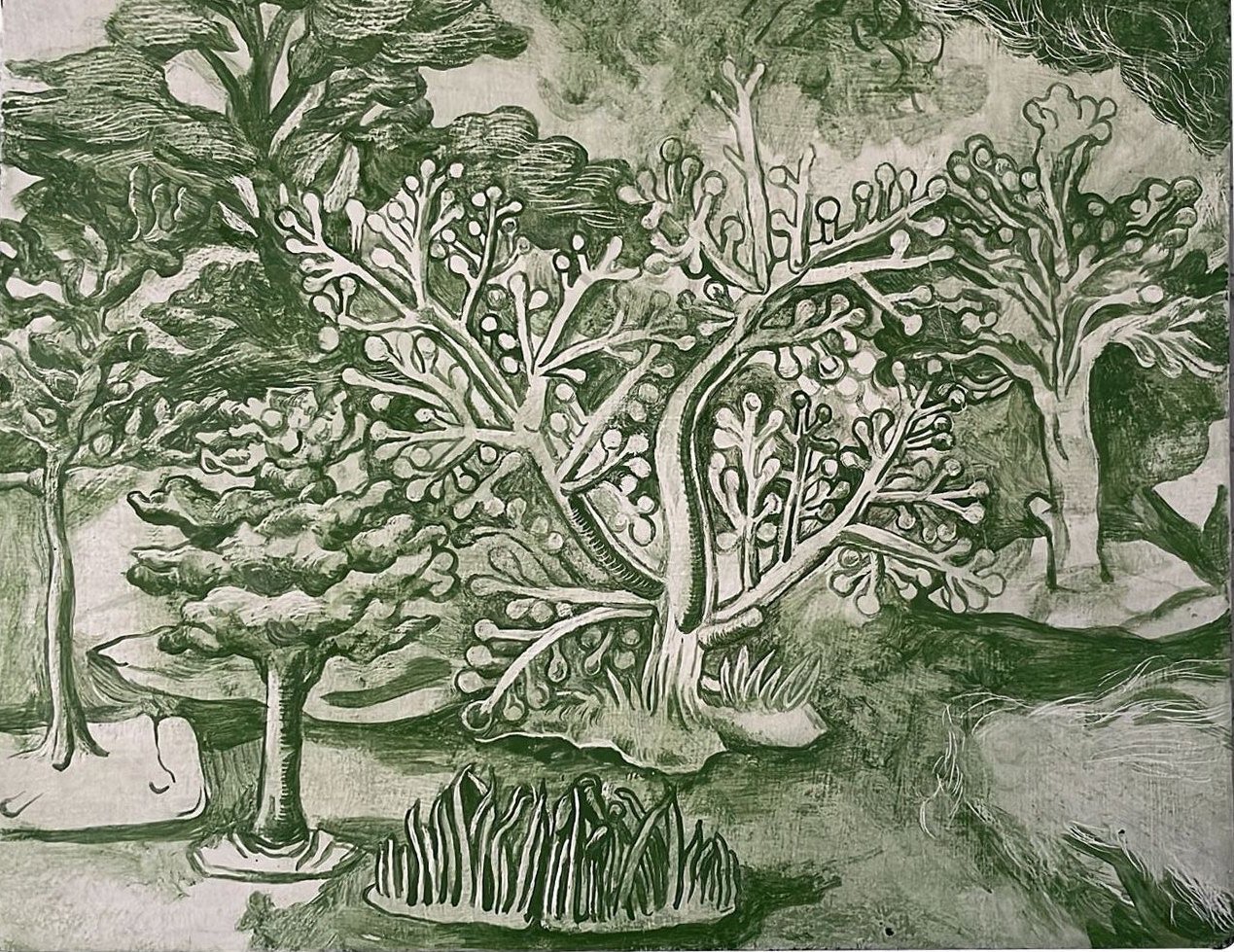

Much of your work explores the contrast between open fields and dense woodland. How do these landscapes shape your creative approach, and what draws you to their duality?

Tom - These two motifs represent two aspects of the British landscape, the familiar terrain of grazed farmland and the beguiling mystery of the woodland.

The paintings are the culmination of many short meanderings out into the countryside near my home where I make quick sketches, notes and sound recordings to use later in the studio. I often carry my easel, paints and canvases and work directly from life. While outdoors I am fully present and responsive to my surroundings. Subsequently, studio work allows me to move beyond the immediacy of direct observation, utilising memory to create images faithful to my experience.

You emphasise working directly from observation outdoors. How does the physical experience of being immersed in the landscape influence your mark-making and artistic decisions?

Tom - Over time the space opens up around me and reveals little nuances. I start to notice things within its’ thickets and hedgerows that I am observing and experiencing there and then at the moment. I get very excited about what my eyes are seeing, and I begin putting marks down very quickly. Often my eyes are wondering around so fast that it is difficult for my hands to keep up. My hands almost shake with excitement at trying to extract these glances and put them down in colour.

The themes of folklore and ancient beliefs run through your work. How do you see these narratives informing your paintings, and what role does storytelling play in your practice?

Tom -There is a temptation to over romanticise the countryside as a lost eden, wild and overgrown. I think this notion is quite dangerous as it removes us from the reality of life in the countryside. It seems to be a knock-on effect from a Victorian era approach to observing the landscape through an urban lens. The reality of people who live on the land is rarely ever bucolic.

I am interested how various communities over time have used stories as a way to understand the landscape. These stories mutate, warp and are elaborated upon over time. They are difficult to be dissected and understood, but leave room for doubt and uncertainty. I like to think my paintings do this too.

There are serendipitous fragments from these stories that culminate in my mind while I’m outdoors working which don’t always permeate onto the canvas, but I like to use them to build a sense of place in my memory. For instance, there is a story (I can’t remember which one) about screaming witches in a deep thicket that came to my mind while I was painting in a hazel copse. The wind was fierce and I could hear something that resembled the screams until I realised it was the branches of the canopy rubbing together.

4. You completed your Postgraduate Diploma at the Royal Drawing School. How has your education there shaped your approach to painting and printmaking?

Tom - The Royal Drawing School was a fantastic opportunity for so many reasons. I was lucky to work alongside a lot of very talented artists in a nurturing and encouraging atmosphere. The guidance and advice from the tutors was invaluable. There was an element of play that I was so nourishing. I think they embed this in all the students there, which is why so many alumni are still practicing artists, artists who are continually questioning their motives and processes.

You talk about reconnecting people with nature through your paintings. What do you hope we take away from your work in terms of our own relationship with the land?

Tom - I hope my paintings mimic the experience of being in nature, dwarfed by the immensity and grandeur of the space and I hope it encourages people to enjoy the quite moments when one is alone in nature.

You are a trained carpenter / cabinet maker, -we are excited that you’ll be bringing some of your more conceptual pieces to draw from at Weald Contemporary’s Drink and Draw Session in Chichester on 5th March. Can you talk a bit about these pieces and some of the other sculptural projects you have carried out using your these skills?

Tom - These were made in collaboration with my wife Kate. For our hand-fast ceremony we wanted to liven up the stage of the village hall and transform it into an immersive ceremonial outdoor arena. I built two privacy screens comprised of three panels which we each painted the landscape of our ancestors (Austrian mountains for me and the undulating hills of Oxfordshire for Kate).

We originally wanted the ceremony to be outdoors so I painted a backdrop curtain of the Sussex landscape, where we live now. We also looked into having our ceremony at the Rollright Stones in Chipping Norton as the hand-fast ceremony is a pre-Christian tradition, so we built a series of standing stones on the stage to manifest this. This has been the greatest collaborative and immersive artwork Kate and I have made to date!

Meg Buick

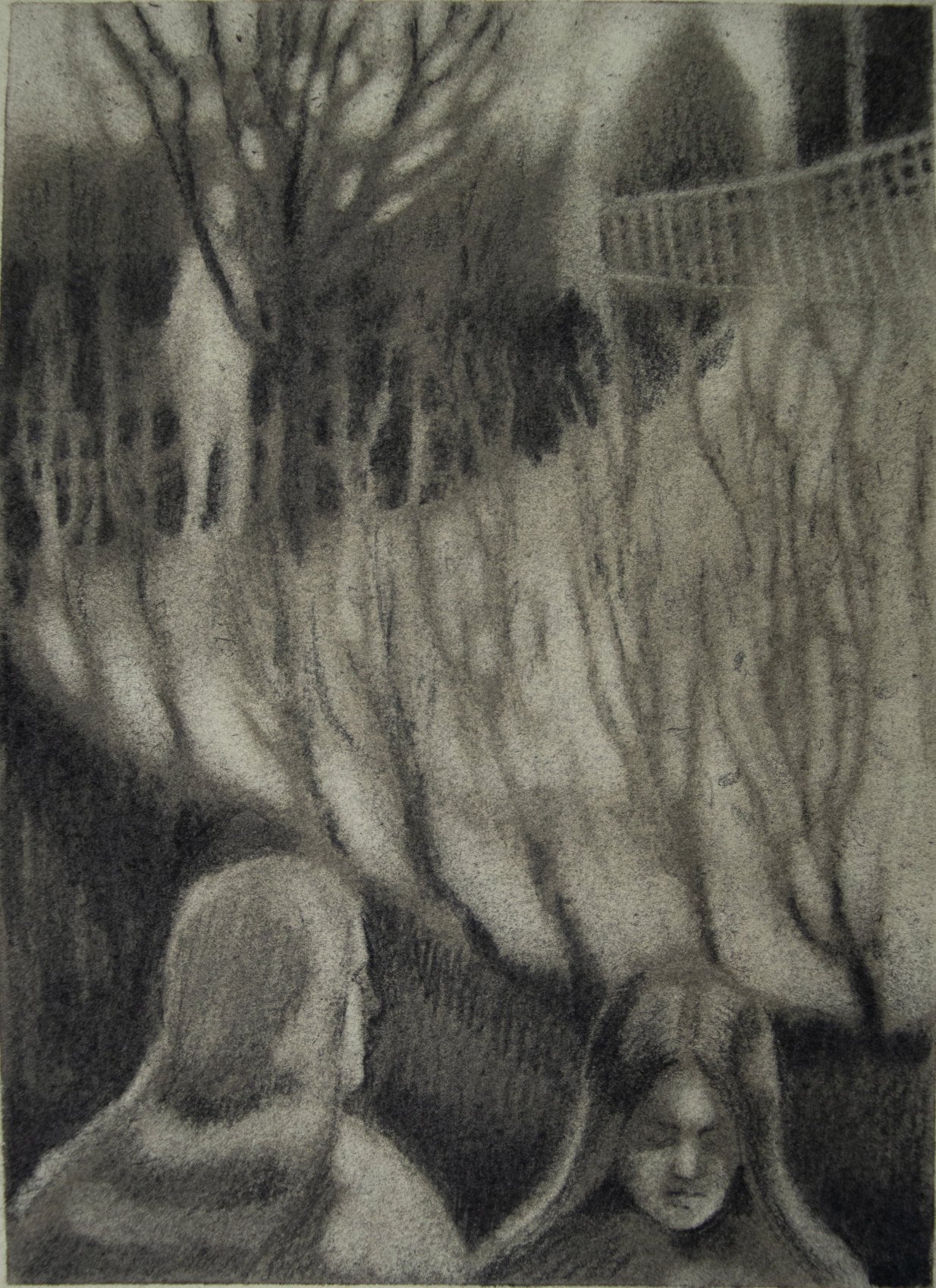

Meg’s pieces for Under the Laurels explore the motif of a single figure within a landscape, whether represented by a person, an animal, or a solitary tree. This approach speaks to themes of solitude, simplicity, and the sublime. Her ability to reflect ambivalence—a sense of beauty and loss—is deeply influenced by the environmental crises of our time, making her work both poignant and relevant. We caught up with meg to discover more about her life and influences.

Meg’s pieces for Under the Laurels explore the motif of a single figure within a landscape, whether represented by a person, an animal, or a solitary tree. This approach speaks to themes of solitude, simplicity, and the sublime. Her ability to reflect ambivalence—a sense of beauty and loss—is deeply influenced by the environmental crises of our time, making her work both poignant and relevant. We caught up with meg to discover more about her life and influences.

Meg Buick, Under the Boughs, Egg tempera on paper, 50 x 70 cm, 2024

Meg, Your work often reflects a balance between beauty and a sense of unease, particularly in your portrayal of the ‘natural world’. How does this duality come through in your pieces for the Under the Laurels exhibition?

Meg- It’s not something I set out to explore in my paintings, but I think it emerges. It’s impossible for anyone who is following the mass scale destruction of the environment to look at the so called 'natural world' without some sense of loss. But it’s also a huge source of beauty inspiration and solace, and I think the ambivalence I feel comes across in the work. All of these pieces explore the motif of figure in landscape - I think I’ve always been interested in the motif of the single figure, sometimes with something standing in for the figure - another conscious being like a bird or a horse - or sometimes a different singular motif like a tree or a house. The single figure could be seen as lonely, or isolated but I think I’m more drawn to its potential to suggest solitude, simplicity, or an experience of the sublime.

You’ve experimented with various media, from painting to etching and lithography. Can you tell us more about the techniques you use and how they come into play?

Meg- really happy to just tack between materials, I think they all feed into each other. I’m a painter really, and when I go into printmaking I can tell that I lack some of the basic patience and attention to process that makes for a very good technical printmaker, but I get so hooked on the end result that I stick it out for a while , and eventually give in to it, and it teaches me to be a more patient and virtuous maker! Then suddenly I get fed up and go back to painting, but the marks and quality of the prints inform the painting process.

At the moment I work a lot with monotype and egg tempera, using them as a ‘ground’ for pastel and pencil and oil paint and other mediums. As well as the practical advantage of fast drying times and low toxicity, I am interested in Nancy Spero’s rejection of oil paint as the male, canonical medium, too heavy with the patriarchal history of painting. I am also interested in the historical significance of egg tempera, as one of the earliest painting materials, and the way in which the material itself can connect the works to the ancient origins of painting.

Meg Buick in the studio

Your images are sometimes described as ‘ghostly’ or ‘fragmentary.’ How does this style of partial revelation or obscurity tie into the broader themes of the Under the Laurels exhibition?

Meg- thing I find interesting about Carrington’s work is how varied it is. She doesn’t seem to have settled on a particular style or subject in the way that the art market generally favours and rewards. I think I read that she stopped signing her pictures at some point, which could imply that she freed herself from the need of external validation - I don’t know enough about her to know if that is true and I don’t want to romanticise her life - it sounds like she was fairly unhappy and it wasn’t an easy time to be a woman. But that kind of rejection of convention seems connected in a way to the rejection of the art world pressure to produce a very logical, coherent body of work . She could paint in a kind of classical realist style but chose to work with glass and silver foil, she seemed willing to let go of some of her training, and that’s interesting to me.

My work is probably fragmentary, I don’t want it to have an obvious narrative, but to remain connected, more like a series of stanzas in a poem. So I am very interested in this element of her work, the separated moments and connections between things, without trying to pin everything to the same narrative arch.

Meg Buick,The Crossing, Monotype and pastel on paper, 50 x 70 cm, 2023

Thomas Compton

Influenced by folk customs, the Arts & Crafts movement, and artists like Paul Nash and Dora Carrington, Compton’s work explores the interplay between intimate personal mythologies and broader cultural archetypes. Recurring motifs, such as the wooden horse, serve as symbols of familial memory and myth, inviting viewers to reflect on the fluidity of time, narrative, and identity.

Thomas Compton is a contemporary artist whose work bridges analogue and digital techniques to craft imagery that feels both modern and timeless. Through meticulous silkscreen printing and experimental layering, his pieces blend personal history, mythology, and storytelling, questioning the reliability of memory and the evolution of narratives over time. Influenced by folk customs, the Arts & Crafts movement, and artists like Paul Nash and Dora Carrington, Compton’s work explores the interplay between intimate personal mythologies and broader cultural archetypes. Recurring motifs, such as the wooden horse, serve as symbols of familial memory and myth, inviting viewers to reflect on the fluidity of time, narrative, and identity.

Your work often combines digital and analogue processes in ways that feel both modern and timeless. Could you walk us through your image-making process for the prints featured in "Under the Laurels," and how it relates to this blend of methods?

Thomas - That’s quite the compliment, thank you! The intention for a project determines many of the process based choices made during image-creation. For this series of prints, I alternated between functional and more freeform approaches to making. Drafting work by hand, scanning and manipulating these alongside haptic digital textures within evolving compositional frameworks sets precedent for the linear sense of narrative necessitated by the graphic novel. This more structured approach initially positions my medium of choice, silkscreen, as a functional output, but printed work I’ve found, thrives within looser constraints and a wilfulness to let the process enact its own agency away from one’s own act of implicit creation.‘Turin Spring Dance’ borrows layers from different artworks in a manner that generates compositional interest beyond my initial capacity to have crafted its exacting effect. A cyclical quality in reading the imagery suspends the initially linear narrative and opens broader possibilities of perception.

The narrative behind "The De Chirico Horse" is both deeply personal and semi-fictional, weaving in family history with a sense of myth. How did you balance fact and fiction in creating these pieces, and what draws you to stories that blur the lines between the two?

Thomas - I think the resonance of a story like this to people is in its recounting. We, who have close family and/or friends have all more than likely heard anecdotal word of mouth stories that just naturally filter down. These stories morph with their retelling and it opens up epistemological and metaphysical questions around the nature of truth. Balancing fact and fiction, although a useful narrative mechanism doesn’t necessarily capture the aura of a story, which I find a far more engaging pursuit.

Thomas Compton, Turin Spring Dance, Screen Print.

Can you talk a little about your studio and your working process?

Thomas - A piece of kit essential to my practice is the silkscreen printing bench. It takes up a lot of room in the studio, emblematic of its importance to my practice. A hand pulled mechanical arm holding a squeegee pulls ink across paper, finessing exact pressure and movement over each pass. Silkscreen requires competency of the technical variables, which are wide and borderline alchemical. My approach to the printing setup is meticulous and requires patience, but beneath a squeegee’s blade, artworks that sometimes have taken months to produce are realised. Beyond the setup, within a work’s creation, I like to weave in opportunities to experiment, to stumble upon moments of the unexpected.

As an artist influenced by folk customs, myth, and the Arts & Crafts movement, how do you see these elements playing out in "Under the Laurels," especially in conversation with the works of Paul Nash and Dora Carrington?

Thomas - Just as Carrington and Nash are conduits to these themes in their own works, the group of artists gathered in “Under the Laurels” have likewise infused their own implicit sense of relationship to the landscape and figures that inhabit them. Nash’s works more overtly suggest that nature, mythology, and the past are inextricably linked, and the landscape itself becomes a backdrop where ancient myths and modern concerns coexist as a repository of memory. There is something characteristically soothing in this calcifying attitude, but I find myself as engaged by the sense of beauty and focus on the intimate that Carrington breathes into the relationships and the explicit inner world present in her works; they are personal mythologies that she creates. My sense of practice is almost certainly a mediation of these ideas, a sentiment perhaps shared by my fellow exhibitors.

Your art is shaped by a fascination with the "provenance and degradation of story through “authorship." In the prints from your graphic novel, how do you see this theme coming to life? - What do you hope viewers take away from these layers of inherited and evolved narrative?

I’ve found that people typically share deep lines of affinity to stories felt personally or by those they care for. It provides a semblance of identity, that I am one of many before me. The provenance of the graphic novel’s story starts with my great- grandfather, but by nature of degradation; the story not being written down and being retold down the family line three generations now, the malleability of its truth comes into question. Does this fact change my feeling of affection for the story? No, the imperfection of its degradation makes it more relatable. The same can be said of the prints, they are vignettes of layering that give semblance to what might have happened, not what absolutely must have.

Thomas Compton, Ferrara Evening Dance, Screen Print

Much like the landscape paintings of Carrington, the imagery in "The De Chirico Horse" feels both dreamlike and rooted in history, with anonymous figures moving through expansive landscapes. Can you speak to the symbolism of the wooden horse and how it connects to the emotional and narrative core of these pieces?

Thomas - The aura of the carving, much like the creation of the prints illuminates and is ode to the story encapsulated by its presence. The carving serves as motif, both as spiritual guide to the familial recount of the mythology garnered in the graphic novel, but also as homage to the animal’s presence in many De Chirico works. I too seem to gravitate back to the presence of the horse in my work somewhat subconsciously. A new piece in the works, rather in the lineage of Nash’s lithograph ‘The Landscape of the Megaliths’ (1937), but rather more intimate in nature and aligned to Carrington’s ‘Fairground at Henley Regatta’ (1921) focuses on the mythology around the stone barrow Wayland’s Smithy. The legend recounts the blacksmith turned farrier god Wayland shoeing horses tethered outside the confines of the barrow on being left a silver coin.

Freya Croissant

Brighton based Freya Croissant is an artist whose work weaves together memory, emotion, and natural landscapes through a harmonious interplay of colour, light, and texture. Rooted in a deeply personal exploration of the environments that have shaped her, Freya's practice spans painting, drawing, and textiles, creating layered compositions that evoke intimacy and tenderness.

Your work seems to invite us into the dream-states of childhood and play. Could you share what memories or experiences inspired this sense of wonder and exploration in your latest work?

Freya- In the last four years I've been on a bit of a journey exploring my relationship to Cornwall in an ongoing body of work ‘Remembering Places Once Trodden’. Conjuring feelings of grief intertwined with memories of childhood naivety and fearlessness. These pieces serve as both reflections and recordings of the North Cornwall countryside the landscapes that shaped my early years. So I’m certainly thrilled this is how you have seen my work.

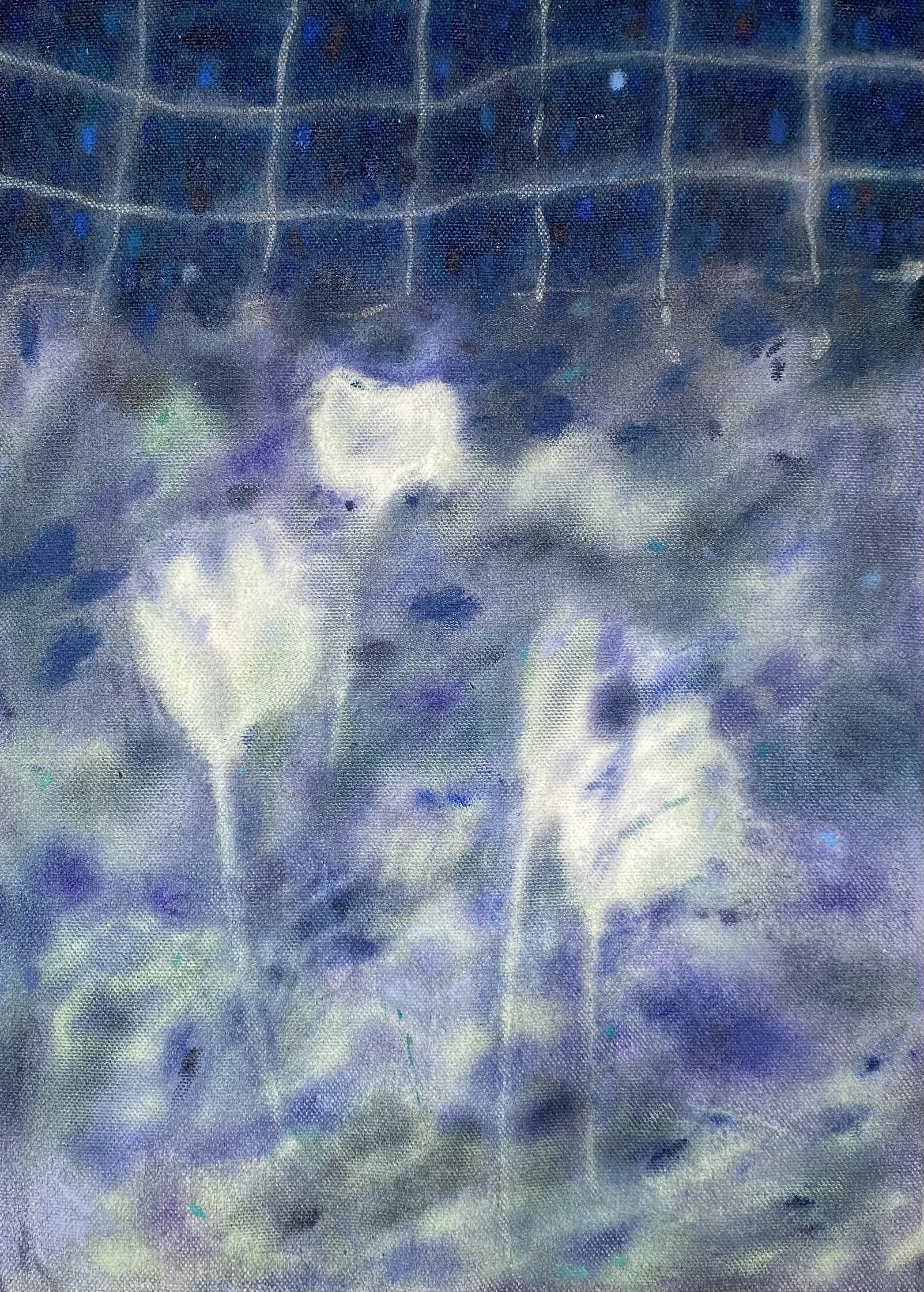

Your work often blends the natural world with intimate, personal spaces. How do you approach translating these elements from your surroundings into the pieces you’ve created for Under the Laurels?

Freya- Since moving to Brighton I have been trying to draw and paint from my immediate surroundings more. I think this is because I’m much more inspired by being near the South Downs coastline. In my painting ‘Tulips outside St Peter’s’ this was a turning point for including man made structures into my images. I would usually shy away from anything rigid and man made but there has been something really pulling me to the repeat patterns of fencing. It’s such a silly little thing but I have been really enjoying looking at it!

Tulips Outside St Peters, Oil and bleach on stretched canvas

You’ve mentioned before that walking and being in nature are essential to your creative process, is there locations you work from regularly?

Freya- Since moving from London to Brighton this year I have been drawing lots around the downs. I have family in North Cornwall so growing up I spent a lot of time down there. There was one particular walk called ‘lovers walk’, winding down from my grandparents bungalow high up on the cliffs to the beach. Passing through farmland, a shallow river, little woodland areas and opening up onto the slate clad beach.

Could you talk about light and how working in different settings influences your use of colour, light, and texture?

Freya - I’m definitely happiest when I’m drawing / making outside. Sadly my studio doesn’t have amazing lighting so I’m often running my paintings out onto the street to check my work. Light has a huge impact on my ability to focus on my work and enjoy making, so when the weather permits I’m out on that side street!

Your art often reflects a sense of solitude and introspection. How do you think this sense of personal space and contemplation resonates with the broader themes of Under the Laurels?

Freya - I am so excited to be included in an exhibition which is exploring the Bloomsbury group. I take inspiration from their decorative approaches & freedom to making, politics and life. A major influence of mine is Vanessa Bell, particularly her use of colour.

How do you approach your palette?

Freya - Colour is possibly the most important part of my practice. I became fascinated by colour theory and the science behind colour being a learned experience whilst studying. I try to be true to my memory with how I portray light and colour, this is why i think my palette is often soft with injections of bold blues, pinks and reds. These childhood colour associations seeping through.

Freya’s studio in Brighton, Sussex.

You work across multiple surfaces—from paper to board to canvas—with what feels like an experimental confidence. How does the choice of medium impact the way you approach each piece or idea?

Freya - The way I approach my painting came from when I was studying Illustration and I discovered soft pastels. I fell in love with how I could blend and blur & blend colours and shapes. Although I love experimenting with different textiles practices I do feel very content with a lightly primed canvas. Im always pleased by how the canvas soaks up the oil a little and I can work in endless thin dreamlike layers.

There’s a strong sense of layering and process in your work, often revealing past versions of an image through faint marks or uncovered lines. Could you describe what draws you to this recursive, storytelling approach?

Freya - I work from memory a lot of the time or at the least from drawings which are often remembered so I am glad that these works come across like this. They are me processing my memory of that place and time.

Your work often contrasts soft, imagery with the vastness of landscapes. How do you balance these playful, day-to-day inspirations with the more profound themes in your work?

Freya - My memories of Cornwall scattered over the last 20 something years have become a feature in most of my work. Even when I’m not painting or drawing them directly. I think simply the process and rhythm I got into when I first started working this way has had a huge impact on my practice. Complex familial relationships, personal development and set backs a defiantly play a role in my paintings but I don’t tend to think about these too much. More how the colour I remember at the time made me feel - which in turn I suppose reflects my wider feelings towards my environment.

Your pieces seem to capture the life cycle of an idea, evolving through layers of color and line over time. Could you elaborate on how time and the evolution of thought play a role in the creation and completion of each piece?

Freya - I think this really comes back to working from memory and mentally unlocking the layers of my memories and the different iterations of them.

Scott McCracken

Introducing Scott McCracken: A Study in Artistic Balance

Scott McCracken’s work masterfully balances structure with spontaneity. By deliberately avoiding traditional subjects, his paintings emerge organically, animated by a sense of freedom and evolution. Working on multiple pieces concurrently, McCracken fosters a dynamic exchange of motifs and ideas, uncovering surprising connections and ensuring each work achieves an essence that feels both self-sufficient and alive.

Scott McCracken Photographed by Benjamin Deakin

You’ve mentioned in the past that placing restrictions on your practice, like avoiding the depiction of people or objects, has helped you create more authentic work. Have these restrictions evolved over time?

Scott - When I said authentic, I maybe should have said unforced. I thought I was trying to find a way of making paintings that I could sustain over a longer period but, with hindsight, I think that was a way of buying myself time. There’s so much freedom and liberation already in making a painting, it’s helpful to place some kind of limitation on yourself and the work. But after a while, a restriction can become a convention or a trope or a formula, so they need to evolve. These initial restrictions have changed organically over time, I’m almost not conscious of it. For a while, the shapes and the spaces within the paintings had to remain flat, but then they started to inflate, so a circle became a sphere and so forth. This allowed the pictorial space to open up much more; it’s continuing to expand now despite the paintings remaining on a smaller scale and the motifs flattening out again. For several years, I exclusively worked on the one format and orientation of support. I needed that continuity. But then I lost interest in that modularity and wanted a new manoeuvrability, even if that meant reducing the canvas size. At present, I’m far more receptive to allowing nameable, or almost-nameable motifs, into the paintings in a way that I would have vehemently rejected before.

Your process involves having multiple paintings in progress simultaneously, I believe it’s often up to 15 or sometimes even 20. How does this approach affect the development of your ideas, and do your feel it allows for or encourages any unexpected connections between pieces?

Scott - I move the paintings around a lot, move them between being upright and lying flat on a table. Elements can find themselves migrating from one painting to another. Working on a small scale has allowed me the opportunity to be able to not only work on multiple paintings at a time, but to quickly move between them and to look at them simultaneously. Simultaneous and comparative looking is important for me in the studio. I occasionally bring out older works and put them up as well. So surprising connections are often discovered not only between current paintings but older ones too. Often, it’s other artist friends who visit the studio who make these connections rather than myself, as I can be too close to what I’m doing. It often feels like my paintings have their own ideas and I’m just trying to keep up with them. People tend to think that by working on so many small pictures, it must mean that one can be less precious than working on bigger canvases. But it’s not really about ‘preciousness’, it’s about giving each painting a certain level of care and attention. I’d like to think I give my paintings that.

Can you talk about how you recognise when a painting has reached the point where it stands alone and is that the same as it being finished?

Scott - I find it’s healthier for the paintings not to be thought of as existing as either finished or unfinished. It becomes too binary, as if the painting is either switched on or switched off. I find that a painting can exist in and as different states of being. It’s more about finding the core, or the essence of it, and that’s when it becomes active. Animated. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s finished but it’s found itself. Or, more accurately, it’s found one version of itself where it can exist in the world independent of me. I never know what a painting is going to do until it’s been made. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how making a painting is the act of searching for something. There is some sense of where you may end up, but only very generally. In making a painting, you’re searching for the specific in the general.

Do you find that working within certain limitations—such as size, form, or colour palette has been a driving force in your work?

Scott - I certainly needed those restrictions around 10 years ago. And because of those limitations, I’m making the paintings I am now. Those restrictions are still deeply felt in the work, even if they can’t be so easily located. It’s definitely been a trajectory, although not necessarily a linear one. For a while, inhibiting the paintings was helpful as it meant I could focus on fewer elements and try to find out what sort of work I should be making. At the moment, I’m feeding them more with what I allow myself to put into them, there’s now a lot more to draw upon. There still aren’t narratives as such, but there could be implied scenarios in some of them. I intermittently flirt with the idea of making bigger paintings, but I don’t think the work as it exists now necessarily wants translated onto a larger scale. Colour has always been tricky for me. The fewer colours I use in a painting, the more important those colours have to become and the more they have to do. I want each painting to feel as if its colour is somehow natural to it rather than having been simply deposited there.

You’ve spoken about your fascination with artists like Giorgio Morandi, Pierre Bonnard and Prunella Clough. How have these influences informed your painting?

Scott - Ernst Wilhelm Nay said “paintings come from paintings, the work of the painter exists within this continuum.” That sentiment resonates with my own experience, as painting comes as much from painting as it comes from life, probably even more so. With Morandi, he’s endlessly fascinating despite his insistence and reliance on such modest objects to paint from. There is a silence embedded within his pictures. And his edges between forms are both assured and hesitant. With Prunella Clough, it’s her attitude as an artist but also how that attitude was reflected within and through the work she made. Something was being broken down and remade anew.

Many of my paintings only appear after being overworked and undone. It takes time for that to happen and can’t be hurried along. Looking at a Bonnard painting is a complete experience where you don’t really want to stop looking at it. To go back to my earlier point, his colour always feels natural and never forced. Even the earlier atypical darker denser paintings from the 1890s I get a lot from. But there are so many artists whose work I look at for lots of different reasons, particularly paintings that have been around for a while and had time to settle, so from around the late 19th century through to the second half of the 20th century. Artists like Francis Picabia, Arthur Dove, Betty Parsons, Serge Charchoune, Lee Lozano, Bruno Goller, Rene Daniels.

Your practice seems to involve a lot of spontaneity, especially in the way you reconfigure motifs. How do you strike a balance between planned structure and improvisation in your paintings?

Spontaneity and improvisation can be quite fundamental components, but there has to be something else that the painting is reaching for. It can’t just be moments of spontaneity, the spontaneity needs to attach itself to something that is more fixed, even if it’s ambiguous. That’s one of the fantastic things about painting, it can contain different and opposing principles or forces. It thrives of them. Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about what is being pictured in my work. Picture-making is important. For a long time, I was referred to as an abstract painter making abstract paintings. I can understand why but I never thought of myself, or the work, as being ‘abstract’. I was making paintings, and they looked the way they did almost by happenstance rather than coming from any kind of critical position. But then I started to become much more interested in still life and landscape painting. To be clear, I was interested in landscape painting rather than landscape. So, I began to occupy a terrain within painting that I could navigate and part of that was the notion of picturing something. My earlier paintings were highly structured, possibly even over-structured. The work has travelled from structure towards an amorphousness despite there now being specific motifs that can be identified and named. I’ve found there’s more of capacity for improvisation in the nameable than in the unnameable.

Photography by Benjamin Deakin

How does your studio environment affect your creative process, would you change anything if you could?

Scott - I’m very fortunate with the studio I have right now. A few months ago, I finally got myself a studio sofa and that’s meant I’ve spent more time sitting down than I would have done before. It sounds quite trivial but a consequence of that is I probably paint less but look a lot more. Having said that, it’s also difficult not to imagine a potential future studio and what that could be like. I’m probably not alone in saying I’ve thought about a larger studio with more natural light and better storage. But the studio I’m in right now is the best studio I’ve had, and I think that has had a positive impact on the work. The environment affects the routine and the routine affects the making-process. I occasionally go to the studio and don’t do any painting, I just like being there, being in what I consider to be the paintings’ natural habitat. I’ve been reading more in the studio too, so all of this changes the incubation of the paintings.

What are you reading at the moment?

Lately I’ve been re-reading Clement Greenberg’s ‘Homemade Aesthetics’ and Italo Calvino’s ‘Cosmicomics’. I’m also taking my time working through ‘Talking Painting’ edited by David Ryan. I’ve discovered that reading is good way of moving from the outside world to the inside of the painting so that’s been the first thing I tend to do in the morning when I get to the studio. My preference is to read what other artists write about art rather than theorists and historians, especially as I sometimes write about painting myself.

You are one of the Programme Leaders and a mentor at Turps Art School, and a regular contributor of Turps Magazine, I am yet to meet an artist with a bad word to say about the programme! - what makes it so special?

Scott - That’s very good to know! One of the many things that makes Turps so singular is that all the mentors who teach are working painters – everyone involved spends their time thinking about and making paintings. I often say that Turps focuses on what happens inside the studio and not outside of it. It’s about making the bad work along with the good work at Turps, to accept and embrace it as a vital necessity rather than trying to overcome, evade or negate it.

The important thing is the work itself. It always comes first.

Laura Wormell

Laura Wormell is an artist who skilfully intertwines vulnerability, symbolism, and the surreal. Known for her emotive colour palettes and intricate compositions, Wormell’s work invites us to engage deeply with themes of communication, identity, and perception, challenging viewers to embrace the ambiguity of symbols and forms, and resist the urge to seek definitive answers

Laura Wormell photographed by Julian Hawkins

Many of your works, like Threshold and Hot Gas Hellcat, seem to merge surreal and introspective elements. What draws you to these themes, and how do they reflect your perspective on intimacy and vulnerability?

Laura - I know I respond most to works that reveal vulnerability, whether that be intentional or not. Perhaps it’s a misplaced mothering instinct, my empathy kicks in. I went to see a concert last night of Max Richter’s Vivaldi’s Four Seasons Reworked. It’s a towering piece of music, it has all the virtuoso themes from the original but pulled apart and reordered.

Aside from my own reaction to the music - a piece that manages to be both so recognisable it almost becomes quotidian and yet deeply profound - I found myself imagining the joy and the sorrow of performing this to an audience. No matter how masterful the musicians are, you can see the effort and the concentration, the wordless communication between the ensemble, the bow hairs breaking during the violent passages, the joke between the cellists when they turn the page too soon, the pride across the face of the solo violinist upon completing a consummate passage in the shiniest patent leather shoes. The performance is an attempt to be perfect and yet it is immeasurably more moving by the nature of it being live with the character and nuance of the performers and the moment in time.

Your paintings often feature subtle, emotive colour palettes and intriguing figurative compositions. Could you share a bit about your approach to colour and form and how you see these elements contributing to the atmosphere of your pieces?

Laura - I learnt to play instruments as a child and music has continued to be a very important part of my life. Like making music, colour is sometimes intuitive and emotional, sometimes more technically informed. The instinct is very closely related - there might be a quote or sample of colour that I want to incorporate in a more conscious way - like using a particular sound in a composition from somewhere else, whereas sometimes the choices are more irrational and emotional in the same way as having a fondness for the key of D flat major. Leading on from this, I approach form and composition in a similar way - I very rarely work on multiple paintings at once - unless there is some serious drying time to be got around. Each painting has its time and its tempo which is unavoidably bound up in my own preferences for that period.

Your art often invites the viewer into a personal, almost dreamlike world. How do you find the balance between personal storytelling and creating open interpretations for your audience?

Laura - I read an interview with the writer Alberto Manguel in which he describes the reader as the real author of a text. The writer indeed writes, but the words “remain in a sort of limbo… until whatever has been written is transformed by the eye of the reader into whatever the reader sees in it”. Anyone who makes anything - painting, music, dance, poetry - is desperate to communicate something. But there is always a failure to be able to, by the tools we have available, which creates a gap between the maker and the viewer. This miscommunication or approximate translation is where the most interesting stuff is. It means a work can have life again once it is completed and leaves the studio.

To use another reading analogy, I have read Jane Eyre at multiple times in my life since my first encounter with it when I was about 14. It’s a very different book for me now. Painting is the same, the act of making the work and the thoughts that drove me to do it are completed once it leaves the studio. My own relation to the object I made is also transformed - opened by the passing of time.

With your background in both formal art education and the immersive Turps Studio Programme, how have these experiences influenced your work and development as an artist?

Laura- The Slade was an incredible place to be, I met life long friends there who continue to be important influences in both life and art. However, I was very young (like most) when I went to the Slade - and so inexperienced. I hadn’t learnt how to study properly on my own yet, and was painfully lacking in confidence to ask the right questions. Turps felt like a second chance to really engage in my work and learn about my place in my own painting. I had spent a decade after graduating from my BA deepening my inquiry into painting so was in a great position to broaden my knowledge without fearing a loss of moorings.

Laura Womell - Untitled 4

Monotype on card

24 x 19 cm

I was very drawn to your exhibition I Am Your Creature at Asylum Studio over the summer. The intricate fonts and human figures that morph into letters create a fascinating dialogue between body and symbol. Could you share your thoughts on what inspired this exploration of text as an abstract element within the figurative realm, and how you feel the interplay between these forms impacts the viewer’s experience of both the image and its meaning?

Laura - Text had been lingering around in my work for a few years before I began making the work for I Am Your Creature. I had been struggling to truly turn letters into shapes - the words always felt like a didactic message which would exert influence over the figurative aspects of the painting they were on - there is the clue, my use of ‘on’ shows that they felt like a separate entity to the rest of the ‘image’. I really wanted to find a way to make the letters part of the image and vice versa. I had been researching alphabets for sometime and came across a 16th century human alphabet from Bologna that I couldn’t get out of my mind. I started to adapt the figures to suit my needs and so the work began to take shape.

Through the convergence of symbols and imagery, I wanted to see how these fundamental elements of human communication intertwine and influence perception and raise questions about how meaning is constructed and conveyed.

I’m fascinated by the idea that letters, as basic units of language, carry both abstract and concrete meanings, influenced by their form and the context in which they are presented. Simultaneously I’m interested in the role of imagery in communication, and the interplay between the seen and the read.

There was a visitor to the show at Asylum Studios that was very cross that he couldn’t make out what the paintings ‘said’. They were even more incensed that the titles didn’t necessarily illuminate any further. I tried to explain that they weren’t signs or information boards but rather paintings to be looked at, and ‘meaning’ was to be gained this way. In the end, I gave in and read the quotes to the visitor as we walked around the gallery. I don’t think once I had revealed the words it made any difference, they were still just as cross! I’m fascinated by this demand we have of imagery and symbols to generate meaning - when really we as the viewer hold the key.

In Conversation Live -Modern Mud, Chaired by Timothy Hyman RA

To accompany our exhibition Modern Mud at Colonnade House, Worthing, we were delighted to present a sold-out live edition of In Conversation featuring exhibiting artists Leigh Curtis, Benjamin Prosser, and Ben Westley Clarke, chaired by the distinguished artist and writer, the late Timothy Hyman RA.

To accompany our exhibition Modern Mud at Colonnade House, Worthing, we were delighted to present a sold-out live edition of In Conversation featuring exhibiting artists Leigh Curtis, Benjamin Prosser, and Ben Westley Clarke, chaired by the distinguished artist and writer, the late Timothy Hyman RA.

Timothy Hyman, who sadly passed away recently, was a visionary painter, writer, and art historian whose contributions to the art world were profound and far-reaching. Known for his richly narrative paintings and his championing of figurative art, Hyman's work was suffused with humanity, imagination, and a deep understanding of art's potential to connect us to each other and to the world around us. His critical writings, including influential studies on Stanley Spencer, Pierre Bonnard, and Indian art, reflected his intellectual rigor and his passion for the undercurrents of modern and contemporary creativity.

Together, the panelists represented a vibrant cross-section of contemporary painting, each contributing distinct voices to the dialogue around materiality, narrative, and the enduring relevance of figuration in modern art. Chaired by Timothy Hyman, the In Conversation event was not only an illuminating exploration of these artists' practices but also a fitting tribute to Hyman's lifelong dedication to celebrating the richness and diversity of the art world. His presence and insights will be deeply missed, but his legacy continues to inspire.

Cheri Smith

Cheri’s captivating work exudes a tactile intimacy and a deep engagement with the natural world. Using materials like oil, egg tempera, and glue distemper, her practice emphasises the elemental origins of pigments—crushed rocks, plants, and even beetles.

Cheri in her London Studio

Your work frequently explores themes of animality and wildness. How do these ideas manifest in the pieces you are presenting for Under the Laurels?